The first-glance impact is usually represented by an image with simple masses of color, painted with big brushstrokes without much detail, often with soft edges between the masses, such as this haystack painting by Monet.

Typically, “impressionist” images have high-chroma dabs of color that resolve into a larger blurry image. Recognizable small details are conspicuously left out.

We’re told that this is how the eye perceives on the first glance. Let me see if I can simulate this idea using a photographic image. Here’s an unaltered photo of a street scene.

Here’s an “impressionist” take on the same scene (using the Photoshop filter “paint daubs” and a heightened color saturation).

I believe there are some assumptions here that need examining. Does our first impression really look like an impressionist painting?

If I’m really honest about my own experience of vision, my first-glance take on a scene is nothing at all like a Monet. What I see in the first two or three seconds are a few extremely detailed but disconnected areas of focus. Small individual elements, such as a sign, a face, or a doorknob, take on particular importance immediately, perhaps because the left-brain decoding process (seeing in symbols) is so heavily engaged in the first few seconds.

I’ve altered the photo to try to simulate this experience by sharpening and heightening these disconnected elements. What happens in the first few seconds for you? I don’t know how other people see, because I’m stuck inside my own head. Perhaps eye-tracking and fMRI studies can help us to better understand what really happens cognitively in the first few second of visual perception. Maybe it varies widely from person to person.

What I’m questioning is not the artistic tradition of impressionism, but rather our habits of thinking about it. The idea of trying to capture the broad, simple masses of a scene is a valid artistic enterprise. But even though I’m a plein air painter with impressionist leanings, I believe that kind of seeing emerges only after sustained, conscious effort and training, or not at all.

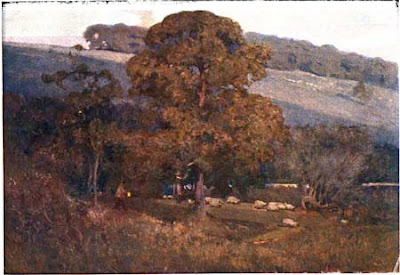

Above: Sir Alfred East, “Night in the Cotswalds.”

Perceiving big shapes requires a deliberate act of defocusing or squinting. These are rather unnatural kinds of perception. When I squint and defocus on a subway, people look at me like I’m insane. Painting teachers know that students don’t see the big masses naturally. They need to be taught to do it.

(Incidentally, this big-mass mode of artistic seeing was very much a part of 19th century academic training, and was by no means exclusive to the Impressionists—but that’s another topic.)

I realize that the term “impressionism” was not coined by the artists, but rather by their critics. In any event the word and that sense of the word have become irrevocably associated with the movement. Of course the word has other definitions, such as the portrayal of transient effects of light and color, or a painting style using short brush strokes, and those meanings of the word are valid.

But the notion that impressionist paintings are accurate representations of our first visual impressions strikes me as false dogma. I’m skeptical of the word when it’s used in that sense.

“Impressionism,” whatever its merits as a mode of picture making, may not describe a universal experience of perception, so much as a particular style of painting.

----------

Related previous posts on GurneyJourney:

Eyetracking and Composition, part 1

Eyetracking and Composition, part 2

Eyetracking and Composition part 3

Introduction to eyetracking, link.

How perception of faces is coded differently, link.